Kids at Work: Latinx Families Selling Food on the Streets of Los Angeles

The Part of Children in Tourism and Hospitality Family unit Entrepreneurship

1

Heart for Children and Immature People, Faculty of Health, Southern Cross University, Coolangatta 4225, Australia

2

Schoolhouse of Hospitality and Tourism, Auckland University of Engineering, Auckland 1010, New Zealand

*

Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

Bookish Editor: Andrea Pérez

Received: 12 October 2021 / Revised: 10 November 2021 / Accepted: xvi November 2021 / Published: nineteen November 2021

Abstruse

This paper reports on a systematic scoping review of peer-reviewed academic literature in the areas of tourism and hospitality family entrepreneurship. Specifically, it explored how and to what extent existing literature paid attention to the roles of children and how children are synthetic, including whether their voices and lived experiences are reflected in the studies. The Extension for Scoping Reviews' arroyo (PRISMA-ScR) was used to identify appropriate articles included in the review. Findings suggest in that location is limited research focused, specifically, on the role of children in tourism and hospitality family entrepreneurship. Children are frequently referred to, in passing, equally family helpers, beneficiaries of inheritance, and as recipients of intergenerational knowledge and entrepreneurial skills. The original contribution of this paper lies in highlighting the dearth of research focused on children's roles, every bit economic and social actors, in tourism and hospitality, every bit well every bit proposing a kid-inclusive arroyo to conceptualising tourism/hospitality family entrepreneurship. This is part of a broader social justice agenda, which is critical in tourism and hospitality inquiry, policy, and planning to privilege children's rights, their participation, and wellbeing.

1. Introduction

Families with dependent children represent a significant proportion of the world'due south population. Children and families form the most of import emotional bonds in human lodge, and information technology is these social relationships that, in office, drive need and supply in tourism. In recent years, at that place has been increasing focus on 'the tourist' and experiences of children, families, and intergenerational wellbeing, e.1000., [1,2,3]. Withal, the bulk of enquiry has ignored the family-related dimensions of tourism businesses [four]. The role of children, specially, is missing in tourism entrepreneurship debates [5]. Notwithstanding, entrepreneurship scholars have studied the role of the family unit in entrepreneurial activities east.g., [vi]. Some entrepreneurship scholars recognized the unique characteristics of family unit firms and adult the concept of family unit entrepreneurship to explore the role that a family unit plays in family businesses, due east.g., [seven,eight,9,10]. Although tourism research has analysed entrepreneurship and family businesses in tourism [4], the part that the family plays in tourism and hospitality businesses has remained limited.

Family unit entrepreneurship in tourism/hospitality is defined every bit the interaction of the family arrangement within a tourism/hospitality business. For example, researchers constitute different types of family relationships are affecting the firm performance. Adjei et al. [11] found that the human relationship between the entrepreneur and their children is the chief factor in the context of business firm operation. Additionally, Bakas [v] emphasises that children play an important economic role in tourism, becoming socialised and educated into the role of entrepreneurs by their parents. Even so, what is lacking in the family entrepreneurship literature in tourism and hospitality is the style in which children influence the entrepreneurship discourse. Children are generally viewed every bit vulnerable and in need of protection and hence, they are often gate-kept out of inquiry. However, this reflects a narrow, developmentally-determined approach to understanding children's capability, which ignores the important economical and social role they can play in family businesses [12,thirteen].

This systematic scoping review seeks to extend that soapbox to a wider understanding of what children hateful to tourism and hospitality from a family entrepreneurship perspective on a global scale. Although the United nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) defines a child as 'a person nether the historic period of xviii years' [14], in this review commodity, we accept a broader definition in line with how each article refers to children. The original contribution of this paper lies in highlighting the dearth of research focused on children's roles as economic and social actors, in tourism and hospitality, as well equally proposing a kid-inclusive approach to conceptualising tourism/hospitality family entrepreneurship. This is part of a broader social justice agenda which we believe is critical in tourism and hospitality research, policy, and planning to privilege children'southward rights, their participation, and wellbeing.

2. Literature Review

While generally, in non-family businesses, the business and family domains are distinct, the unique feature of family unit businesses is that family members, including children, work together for economic purposes. In other words, 'the family unit is not merely a social unit of measurement but also an economic unit of measurement (p. 13)' [xv]. As such, family unit practices and relations between family members, including children, are often performed in the public domain [16,17]. Literature in this space has increasingly taken a gendered lens past focusing on women entrepreneurs in rural areas, including tourism and home-based businesses or 'side-activities' [18]. However, the role of children inside these women-run or family unit businesses is largely missing in tourism and hospitality enquiry.

In family tourism research the parent-child or spousal dyads, alongside parental/maternal perspectives, have dominated [19]. Relatively few studies have explored family unit holidays 'through the eyes of a child' [3]. Small [20] argues the perceived passivity of the child in conclusion making and, consequently, the child's low economic value to the tourism industry, is the most likely reason for this lack of inquiry. This has led to an absence of childhood in tourism research [twenty,21], and up until recently, children'due south views and opinions have been filtered by adults [12,22]. In a similar vein, while hospitality studies have begun to pay greater attention to children, highlighting their role every bit sovereign consumers, eastward.g., [23,24], they are even so treated every bit passive objects (a notable exception is [25]). Still, the notion of the kid equally a passive object is an increasingly dated 1 inside the social sciences in full general, and specifically in the field of childhood studies, where a paradigmatic shift has seen children recognised every bit active social agents, e.yard., [26,27].

Whilst there are methodological and ethical bug to consider when doing inquiry with child participants in tourism and hospitality [28,29], social science researchers have been involving children in enquiry for decades. This focus on the child has not been carried over into the tourism/hospitality field. Although recent research activities are becoming more inclusive of children equally tourism and hospitality consumers, e.thousand., [21,25,thirty,31], there is still a lack of research on children equally tourism/hospitality suppliers. A recent systemic review into host-children revealed that, apart from limited research into kid sexual activity workers, other bug related to children as workers have been neglected [32]. This lack of research extends more broadly to children in host communities or those who alive and work in tourist destinations [33,34].

The exclusion of children is probable continued to pervasive 'protectionist' approaches to kid labour discourses and the stigma that currently surrounds children's piece of work. The term 'kid labour' is, in and of itself, problematic given information technology has emerged to refer prevalently to exploitative and chancy work that interferes with a child's development and education [35]. This is compounded past the way global reporting systems conflate estimates of children working within the family unit and in microenterprises with piece of work that 'by its nature or circumstances, is likely to damage children's health, prophylactic or morals (p. 18)' [36]. The latest global estimates from the International Labour Arrangement (ILO), for case, show that 160 million children were in 'child labour' at the showtime of 2020, and 79 one thousand thousand of those children were involved in dangerous work, albeit no mention of tourism or hospitality is made [36]. These protectionist discourses fail to recognise that children's labour has been disquisitional to economies historically (for example in Africa) and that scholars take tended to treat kid workers as invisible [37].

While international human rights treaties, such as the UNCRC, seek to protect children from impairment, kid labour discourses seem to be solely focused on the exploitative and unsafe aspects of some forms of work with niggling recognition of children'south agency and their right to contribute to and support their families [38,39]. Article 32 of the UNCRC stipulates that State Parties must recognise 'the right of the kid to exist protected from economical exploitation and from performing any piece of work that is likely hazardous or to interfere with the child's education, or to be harmful to the child'south health of physical, mental, spiritual, moral or social development' [xiv]. While the ILO calls for the abolition of child labour [36] and the United Nations' Sustainable Evolution Goal viii.7 seeks to eradicate 'child labour in all its forms' by 2025, little attention has been given to children'due south own interpretation of work, peculiarly within the family, whether through formal or informal employment in the tourism and hospitality sectors. Studies that have collected children'south views of their interest in family labour have often emphasised the positive economic, social, and emotional contribution they make to the family unit and the broader customs despite the stigma often associated with such work [twoscore,41].

Josefsson and Wall [42] argue that, against the backdrop of global policymaking, which is advocating for the emptying of kid labour, some kid advocates, and children themselves, have led grassroots movements to argue for children's rights to contribute to their families, particularly in cases of farthermost poverty in countries in the Global Southward. The African Motion of Working Children and Youth (AMWCY) is i of many emerging grassroots movements that have been formed by children themselves, NGOs, and child advocates to argue for a culturally specific interpretation of children's working rights. Terenzio [43] argues this movement 'tries to encourage children to appropriate their rights by rebuilding them through their ain experience (p. 69).' Kid and youth labour unions have, in some cases, been successful in lobbying for kid rights to work including off-white wages, limited working hours, legislation confronting exploitation, and recognition of their worth and dignity [41,42,44]. This is in line with scholarly developments which indicate to the decolonisation of childhood itself, moving abroad from universal understandings of childhood that fail to reverberate the diversity of children's experiences beyond familial, social, and cultural contexts including inside and beyond minority and majority world contexts [45,46].

Given the complication of the problems surrounding child labour and the prevalent 'protectionist' views of children involved in the tourism and hospitality industry as suppliers [47], the word presented in this paper focuses primarily on children in tourism/hospitality family entrepreneurship to ascertain whether children's own views of their work in the family unit business have been explored in the literature.

This paper aims to systematically review scholarship by addressing three main enquiry questions: (a) How, and to what extent has existing literature paid attention to the role of children in tourism/hospitality family entrepreneurship?; (b) What is the scope of this existing scholarship in terms of themes, theoretical approaches, and geographical locations?; (c) How are children constructed and to what extent are their voices and lived experiences reflected in these studies? The outcomes of this systematic scoping review are to place patterns and knowledge gaps, as well as propose directions for future enquiry on the role of children in tourism family entrepreneurship as function of a social justice agenda.

iii. Methodology

To explore academic scholarship at the intersection of family entrepreneurship, tourism/hospitality, and childhood, we employed a systematic scoping review methodology. Scoping reviews are particularly helpful when mapping relevant literature at the intersection of multiple fields of enquiry and identifying future research priorities [48]. Nosotros employed the Extension for Scoping Reviews' approach (PRISMA-ScR) (Based on the Moher et al.'southward (2009) Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)) to identify advisable articles to include in our review [49]. Following our previous piece of work with this methodological arroyo, we approached the scoping review in a systematic, replicable, and transparent way, including the post-obit steps: (i) developed a well-defined review question; (two) identified relevant databases to search; (iii) identified relevant articles; (4) selected studies for inclusion in the analysis phase; (5) finally analysed and synthetised the information.

In Stage 1, we divers the main review questions we wanted to accost: (1) What is the part of children in tourism/hospitality family entrepreneurship? (two) How are the children in these studies synthetic? (3) To what extent are their voices and lived experiences reflected?

In Phase ii, we developed our search protocol which was guided by a university librarian specialised in systematic literature reviews. In the start instance, a serial of keyword combinations (n = 25) were tested to explore the most advisable way of sourcing studies which addressed our review questions. The inclusion of the word 'labour' or 'labor', for example, was problematic, as manufactures tended to accost child labour and man rights issues rather than family unit entrepreneurship per se see, for example [50]. It was thus excluded from the search, even so seminal articles which focused on the emotional labour of children in tourism and hospitality businesses were included manually in our sample [16,17]. Likewise, the inclusion of composite words such as 'family-owned' or 'family-based' was not deemed necessary as these keywords were picked up individually.

Our final search protocol included all peer-reviewed, scholarly articles published until 26 March 2021 (when the search was performed), which included the keywords: ("famil*" OR "family owned" OR "family based") AND ("entrepreneur*" OR "business organization*" OR "enterprise*" OR "piece of work") AND ("tourism" OR "hospitality") in the abstract or title of the manuscript and the keywords: ("kid*" OR "immature" OR "youth") in the trunk of manuscript. The databases included Academic Search Premier, Business Source Premier, Hospitality & Tourism contained in EBSCO and Emerald. To search the Emerald database, it was necessary to simplify the keywords searched, hence the Boolean search included: abstract:"family" AND (abstruse:"entrepreneur*") AND (abstract:"tourism" OR "hospitality") AND ("business organisation") AND ("child*" OR "young" OR "youth"). But studies with empirical evidence were included in the analysis.

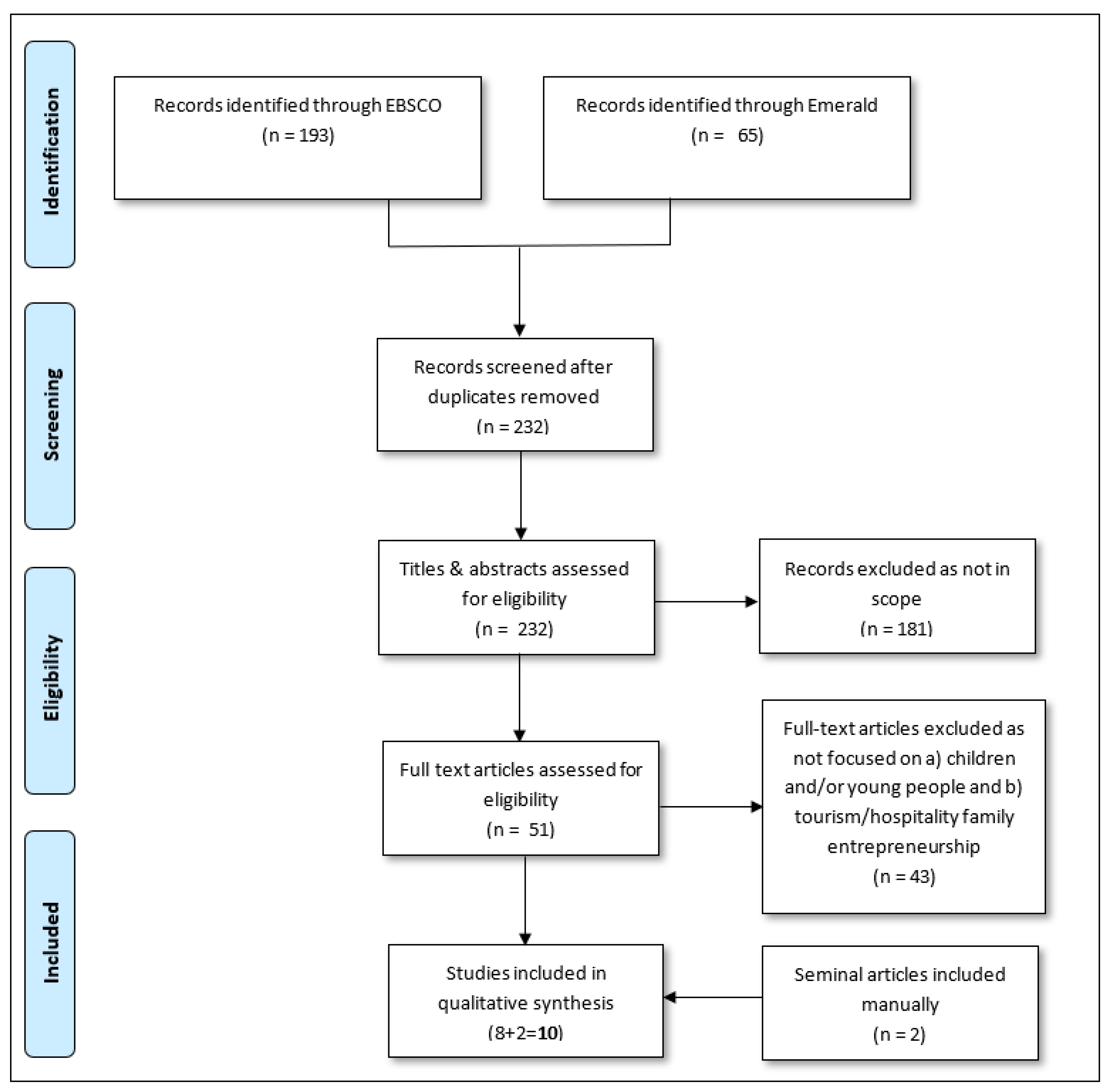

In Phase 3, we searched the databases, which produced 193 records in EBSCO and 65 in Emerald. These studies were exported to EndNote, a reference and bibliographies management software. After removing duplicates, 232 records were screened. In the offset instance, the titles and abstracts of the 232 were assessed for eligibility confronting our inclusion criteria. In this stage, 181 records were excluded equally not in telescopic (meet Effigy 1). Often, systematic database searches capture irrelevant articles, which can be excluded simply by reviewing titles and abstracts, meet [51].

In Phase 4, the full text articles of the remaining 51 manufactures were accessed and screened for eligibility, and a further 43 articles were excluded as they did not specifically focus on the function of children in tourism and/or hospitality entrepreneurship. An example is the Ilberi et al. [52] report, which discusses the family unit status of entrepreneurs (e.g., couples with children) simply does non engage with the function of children in supporting the family business, see also [53]. The Tan et al. [54] written report, in contrast, addresses the nurturing of transgenerational entrepreneurship in ethnic Chinese modest, and medium-sized, family enterprises. However, it does not specify whether this is in the context of tourism or hospitality. Likewise, the study by El-Far and Sabella [55] is interesting as it problematises the ascendant conceptualisation of entrepreneurship past demonstrating how marginalised Palestinian women and their children engage in informal entrepreneurial activities (due east.yard., street vending) as a class of empowerment and resistance to economic adversity, social marginalisation, and political (colonial) domination. All the same, the article does non discuss whether this is situated in the context of tourism. At this stage, seminal articles that were missed during the systematic database search were likewise included manually (northward = two).

In Phase v, the identified articles (northward = 10) were analysed using thematic qualitative analysis. In the first instance, the bibliographic details of the studies were exported in an Excel spreadsheet (e.g., authors, championship, abstract, keywords, publishing periodical). One time the study was analysed, emergent themes were included in the Excel database including, for example, the focus of the study: the role of children in the family enterprise, theories and methods employed, and location of the study. These themes were discussed amongst the research team at regular project meetings to brand sure the assay was accurate. The thematic analysis is discussed in the following findings section and synthetised in Table 1.

4. Results

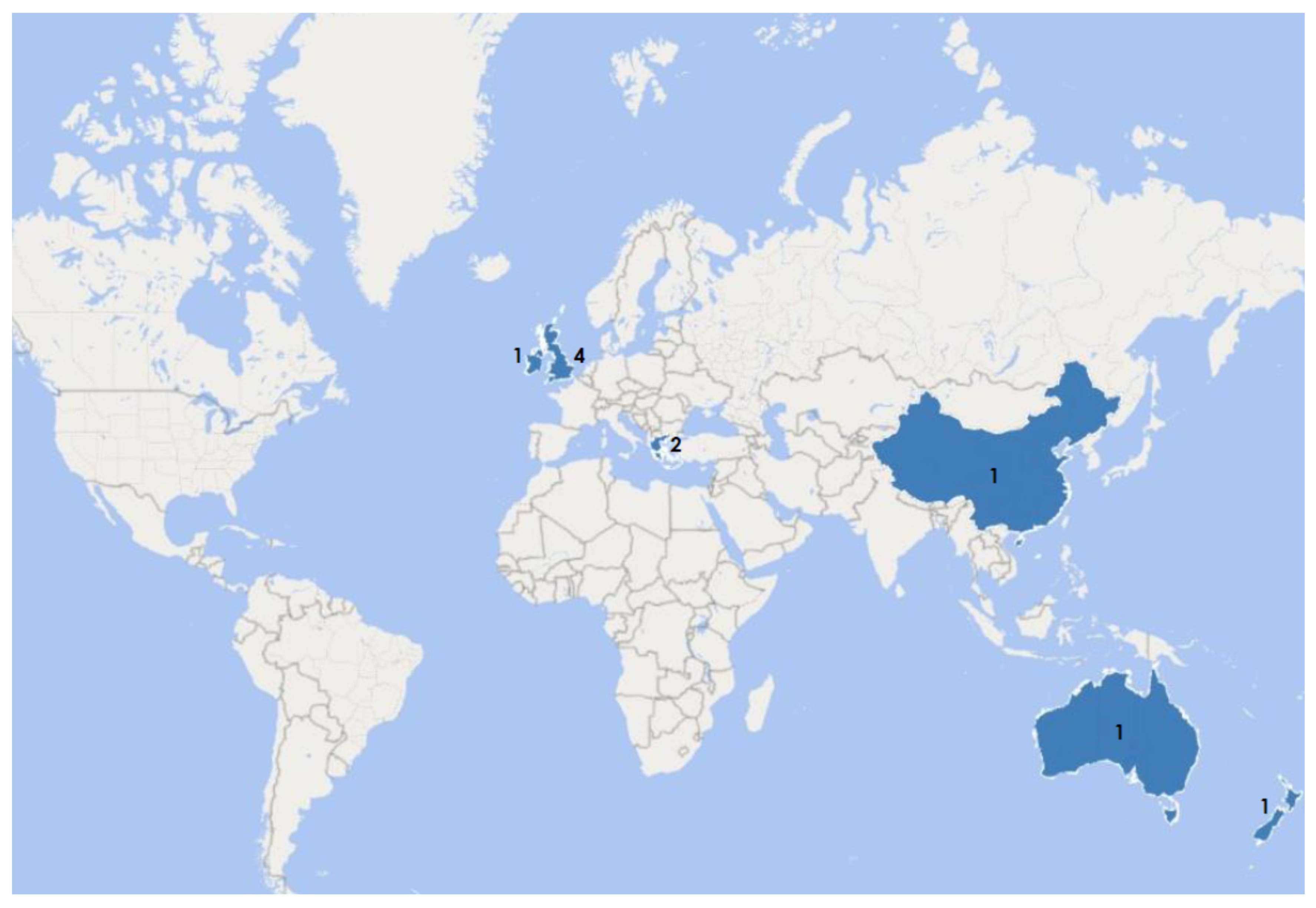

The systematic scoping review employed in this paper revealed that the intersection of family unit entrepreneurship, tourism/hospitality, and childhood is an under-researched area of enquiry. Only nine studies were considered in scope and progressed to the analysis phase, highlighting how the important role that children play in family-owned businesses in the tourism and hospitality industry is oftentimes overlooked and scarcely researched. The articles sourced in our analysis were all empirical, and the majority employed qualitative methods, such as ethnography, participant observation [5], and qualitative interviews [15,18,56,57]. The remaining three manufactures employed a mixed method approach with survey questionnaires and interviews [58,59,60]. The state distribution of the studies, in the sample shown in Effigy 2, reveals that, apart from one study in China, the other studies are based in either Europe or Oceania.

The articles were framed predominantly within the business concern and entrepreneurship literature and often employed conceptual and theoretical models, such every bit the family business development model [58], entrepreneurship theory [15], and behavioural or lifestyle theories [15,18]. Some studies discussed family labour literature [57], resilience and leadership [56], and poverty alleviation, also as social and occupational mobility [59,60]. Notable exceptions to the prevalent business organization and managerial focus of these studies were the studies by Bakas [5] and Seymour [16,17]. The sometime employed disquisitional feminism and a feminist economics lens to explore the gendered parental entrepreneurial roles of Greek women and the role played by their children in supporting the family-owned business organization in the tourism/hospitality sector. The latter employed critical hospitality studies, operation theory, emotional labour, and the sociology of babyhood to explore how families, including children, are on display and 'perform' hospitality in the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland.

The thematic analysis revealed several ways in which children are conceptualised in the tourism/hospitality family entrepreneurship literature, which are discussed in more depth in the following department: children as family helpers, children every bit inheritance, children as learners, and children as social agents. Table 1 summarises the focus of each article in relation to our research questions: (1) what is the role of children in tourism/hospitality family entrepreneurship? (two) How are the children in these studies constructed and to what extent have their voices been reflected in these studies?

4.1. Children every bit Family Helpers

'Children as helpers' in family-endemic tourism and hospitality businesses was the main theme that emerged from the articles analysed. Nigh studies described children's part in the family business organization in fleeting statements while discussing the compatibility of tourism and hospitality entrepreneurship with family life and childcare duties. The report past Basu [15] focuses on the business aspirations of immigrant entrepreneurs from five ethnic minority communities in the Uk, discussing how the particular family life bike phase and the aspirations of entrepreneurs play an of import role in the way motivations and goals are set. There is, notwithstanding, just minor mention of children employed in the family business and no indication of their age, nor inclusion in the research.

As well, studies by Bosworth and Wilson-Youlden [18] and Wilson [58] both mention children in passing while discussing the gendered part of women entrepreneurs in family unit farm stay businesses. Both studies discuss how life-style choices and childcare duties are of import considerations in the motivations of women entrepreneurs in farm tourism. Bosworth and Wilson-Youlden [eighteen] employ entrepreneurial orientation theory, and the theory of lifestyle entrepreneurship, to argue that farm tourism creates new opportunities for women's empowerment through subcontract-based hospitality in Northeast England. Children'southward part in the family business concern is only mentioned in 1 of the women's interviews: "my children can accept a booking" [18] (p. 134).

Wilson'southward [58] study on family-owned subcontract stay businesses in Northern Ireland, employs the family business development model to argue that, unlike other small family tourism businesses, lifestyle motivations take precedence over business growth in farm stay businesses. Wilson [58] discusses how the interest of children from a young age is unique to this form of tourism and hospitality enterprises. The author argues that children'south role in the family business is largely informal and for 'fun' in the early years (due east.thousand., looking subsequently and feeding animals), and and then, it slowly progresses into paid seasonal work in after years.

In the manufactures by Strickland [57] and Zhao [60], children are also seen as helpers in the tourism family business. However, the discussion is approached from a different angle and in reference, specifically, to family labour, poverty alleviation, and the unpaid nature of children's labour. Strickland's [57] written report discusses the operation of ethnic restaurants in regional Victoria in Australia, with a detail focus on the potential benefits of employing family members in terms of labour price reduction. The author argues that employing family members, like children, is a financially viable solution for minor family businesses in the hospitality sector, where labour cost is the most pregnant challenge. The family unit labour that children performed in this study is seen as important in reducing wage expenditures. Children are thus frequently paid lower than award rates, or not paid at all, for the family business to remain financially feasible.

Similarly, the study past Zhao [60] discusses children's roles as helpers involved in unpaid family labour. In the context of pro-poor tourism evolution, the article examines the economic effects of small tourism businesses in rural Guangxi, Mainland china. Because the lack of research on entrepreneurship in the Global South, the article raises interesting conceptualisations of children as working for the 'family rather than themselves' and the fiscal success of the family business [60] (p. 176). Nevertheless, the role of children is discussed in passing while referring to other members of the family, and children are non included in the sample.

Finally, the study by Bakas [5] is unique in that it discusses both the social reproductive tasks (i.e., household chores) and productive tasks (i.due east., replacement entrepreneurs) that children engage with in family-owned businesses in the tourism and hospitality sector in Hellenic republic. Equally such, it volition be discussed in more than depth in the section on 'children equally economic actors'.

4.two. Children as Inheritance

Seminal work in tourism family entrepreneurship demonstrates that just a small minority of family-owned businesses in the tourism and hospitality sector are inherited by children [4,61]. Getz and Carlsen [4] (p. 239) argue that these ventures rarely endure 'through a complete lifecycle' and they often fail or are sold rather than inherited. This is consequent with our analysis, which only identified two studies focused on inheritance issues and children'south office as inheriting entrepreneurs. In the study by Wilson [58] issues of succession are discussed in relation to farm tourism businesses and the legacy that the land represents for the next generation. Empirical evidence from this study, based in Northern Ireland, shows, withal, that in that location was a pocket-sized take a chance of succession or 'passing on the billy' [58] (p. 365). Children were by and large happy to help out when they were immature but were non keen to take on the family business in adulthood.

In dissimilarity, the study by Zagkotsi [59] (p. 191) focuses on the notion of 'intergenerational professional heredity' to underline its importance in the accomplishment of upward social and occupational mobility among Greek tourism and hospitality family businesses. Children are mentioned, in this study, as recipients of the professional person skills and knowledge needed to run the business in the futurity. Zagkotsi [59] argues that children are involved in the family business from a young historic period equally helpers and then, later on, get partners when they are older and start their own families. Families living in tourism destinations thus build 'an intergenerational tradition of professional person occupation' (p. 200), a miracle which, over the years, and across different generations, results in an improved professional and social condition of the family unit members.

These very different conclusions from empirical insights from Northern Republic of ireland and Greece might advise that inheritance issues and professional heredity are considerations that vary across cultural, social, and economical contexts.

4.three. Children every bit Learners

Connected to professional person heredity is the issue of intergenerational learning and conceptualisations of children as 'learners'. Like Zagkotsi's [59] study, show from Hellenic republic suggests that entrepreneurial skills are passed down by parents to their children from a immature age, who, in plow, go young entrepreneurs and economic actors in the productive economy of the family tourism/hospitality concern [5]. Bakas [5] argues that parents accept on a dual office as 'entrepreneurs' operating for turn a profit and equally 'educators' transferring valuable skills and insights to the side by side generation of family unit entrepreneurs.

Intergenerational learning was also a theme in a study based in New Zealand. Kawharu, Tapsell, and Woods [56] explore the connection between resilience, sustainability, and entrepreneurship, from an ethnic perspective, past analysing the leadership roles at a micro kin family level through a tourism business and at a macro kin tribal level through urban land development. Children are referred to in the first case report which explores a small family-based entrepreneurial business organization offering 'village experiences' at Ohinemutu in Rotorua. The authors argue that the historical context in which children were socialised in the 1970s, through straight contact with tourists visiting their village, was a learning experience they carried in futurity entrepreneurship endeavours. Posing for cameras and performing songs in the villages not only provided pocket money for the children only also provided a stage for 'young budding entrepreneurs' to test their 'hosting/opportunity-making/innovation ideas on visitors' through the principle of 'manaaki' (Manaaki means support or hospitality co-ordinate to the Māori lexicon) [56] (p. 30). These entrepreneurial skills would often serve young people well past providing opportunities to travel, gain experience in the tourism and hospitality industry, and and so return and ready family-based businesses, which, in turn, would revitalise and bring prosperity to their communities.

iv.iv. Children equally Social Agents

4.four.i. Economical Actors

It is apparent from the studies discussed then far that children are constructed every bit helpers, inheritance, and learners but seldom as active social agents in tourism and hospitality family unit businesses. So far, studies have not included children in research samples and, in fact, only three studies in our sample view children as social agents able to contribute to family unit-based enterprises in the tourism and hospitality sector. As mentioned, the report by Bakas [five] is unique as it takes a critical feminist economic science lens to explore the gendered entrepreneurial roles of women in the hospitality sector in Hellenic republic. Although it is not clear whether children were directly interviewed during the research, Bakas [5] provides an interesting business relationship of the roles played past children in supporting family-owned businesses. The writer explains how initially children attend to 'social reproductive tasks' (p. 220), such every bit helping with household chores, when mothers are busy with entrepreneurial activities. Subsequently, and equally they grow older, children take on the part of 'replacement' entrepreneurs during the summer flavour, learning important entrepreneurial skills.

Bakas [5] challenges prevalent assumptions connected to kid labour, which describe children as victims and in demand of protection from exploitative work practices. The author argues that while kid labour may be detrimental in situations where children are prevented from achieving important educational goals, in Greece, the seasonal nature of tourism activities is such that children are able to work in the family business during the extended school holidays over the summertime season. While Bakas [v] focuses on the gendered role of women entrepreneurs that has its roots in Greek social and political leader economic structures, she conceptualises children as 'economical actors' who 'actively shape the gendered entrepreneurial landscape by choosing to assistance within the family business organisation or non (p. 221)'.

4.four.two. Involved in Emotional Labour

Studies past Seymour [xvi,17] were included, manually, in our sample, given that they were not picked up past the systematic database search but are particularly relevant to our analysis of children'southward roles in tourism/hospitality family entrepreneurship. The studies are based on empirical bear witness in the hospitality sector in the UK, from a longitudinal perspective, with data nerveless from adult entrepreneurs also as some of their children. The inclusion of children through informed consent in interviews with other family unit members is significant, given that no other study in our sample has directly engaged children in the enquiry process. While the 2015 study focuses more on the functioning roles of families and children on display in hotels, pubs, and boarding houses, the 2005 report makes a clear link to the perspectives and voices of children's emotional labour in family-run hospitality businesses. Seymour [17] argues that children'south emotional labour involved either 'falsely putting on a friendly confront in forepart of guests or, conversely, toning down 'bad' emotions then as not to be overheard by customers (p. 93).' Children'south own interview excerpts describe how they bask the social interactions with visitors, making friends with other children on vacation, and generally beingness around to entertain and be entertained past visitors. Seymour [17] argues that children's social interactions with guests were seen as a 'requirement' in situations where the family business was besides their home.

Seymour [17] depicts children equally active social agents who significantly contribute to the family business through emotional labour and household labour. In so doing, the author describes how children resist and 'subvert' their performance, choosing how they collaborate with guests and the frequency of such interactions. Children often take initiative in employing emotional and physical labour to their advantage (e.g., receiving pocket money from conveying guests' numberless or receiving gifts from guests). Cartoon on childhood studies, Seymour conceptualises children as active agents in negotiating the degrees of emotional labour on brandish in the family-endemic hospitality business and the important roles they play in the success of these ventures. Ultimately, children are not viewed just as future adults but as contributors to family unit entrepreneurship in the present, moving away from more protectionist views of kid labour.

5. Discussion & Conclusions

This newspaper reports on a systematic scoping review of peer-reviewed academic literature in the areas of tourism and hospitality family entrepreneurship. Specifically, it explored how, and to what extent, existing literature paid attending to the roles of children and how children are constructed in this literature, including whether their voices and lived experiences are reflected in the studies. This review paper directly contributes to one of the themes of this Special Issue by exploring the 'silent voices' within family entrepreneurship in tourism and hospitality as part of a broader social justice calendar to promote children's rights, their participation, and wellbeing in the tourism industry. Equally such, it provides new insights into children and families in tourism/hospitality, from a supply side perspective, and highlights previously understudied aspects of tourism. By doing so, it seeks to challenge researchers to consider a more comprehensive view of family entrepreneurship, 1 that includes the voices of children.

Findings of the review propose there is limited research focused, specifically, on the office of children in tourism and hospitality family unit entrepreneurship. Children are often referred to in passing as family unit helpers, beneficiaries of inheritance, and as recipients of intergenerational noesis and entrepreneurial skills. These studies do not include children in research samples and approach family entrepreneurship from an adult-centric or 'adultist' perspective, see, for example, [15,18,56,57,58,59,sixty]. Wall [62] argues that 'adultism' is a deeply ingrained and pervasive lens, or prism, from which we view the world and social realities. While social research has challenged normative assumptions and promoted diverse and intersectional ways of conceptualising reality (eastward.g., gender, ethnicity, disability, class, and sexuality), 'youth' has rarely been considered as i of these social dimensions from which to view and critique reality [33,62].

In the sample of studies analysed in this review paper, children are viewed and constructed equally 'objects' and recipients of skills, noesis, and inheritance, while neglecting to focus on children's ain interpretation of reality and lived experiences of family entrepreneurship in tourism and hospitality. Much progress has been made to meaningfully include children'southward perspectives and voices when it comes to the demand side of tourism east.grand., [3,25,thirty,63]. However, Gram'due south [21] critique of children's passivity notwithstanding rings true when it comes to the supply side of tourism and hospitality, including family unit entrepreneurship. Only express scholarship has focused specifically on the role of children as active social 'agents' who contribute to the family business through household labour [v] and emotional labour, oftentimes subverting and resisting their roles in interactions with guests [16,17].

The neglect of children's lived experiences of tourism and hospitality family entrepreneurship is likely continued to 'protectionist' views of child labour and the stigma currently associated with working children. This is role of a general invisibility of child workers, despite children's labour having been historically critical to economies [37]. While international policy generally condemns kid labour and aims to eradicate child work in all its forms (e.g., Un' Sustainable Development Goal 8.7), in that location is lilliputian data collected to document children'due south own interpretation of work, particularly within the family, whether through formal or informal employment in the tourism and hospitality sectors. Bromley and Mackie [35] contend that such 'universal condemnation' of kid labour requires a more 'flexible approach, which recognises the benefits of children'southward work and embraces supportive protection for children engaged in the lighter forms of work (p. 141)' such as when children have on the part of 'replacement' entrepreneurs in the family business over the summer holidays [5]. There has been a call for more research on children's own perspectives and lived experiences of piece of work [35,41,64] and recognition of their rights to protection from work that is harmful to their wellbeing [35,44].

This review newspaper sought to identify knowledge gaps and provide directions for hereafter research on the part of children in tourism family entrepreneurship as role of a social justice calendar. Children are withal in many cases 'subalterns' [65], and their own interpretations of reality are oftentimes ignored or not considered of import in tourism and hospitality research, policy, and planning [66]. Nosotros suggest moving abroad from prevalent 'protectionist' and 'adultist' assumptions that marginalise children and encompass more child-inclusive understandings of family entrepreneurship. Just as feminism, postcolonialism, and environmentalism have sought to disrupt the norm, and so does 'childism' aim to offer a much needed 'disquisitional lens for deconstructing adultism across research and societies and reconstructing more age-inclusive scholarly and social imaginations (p. one)' [62]. To achieve this, we must overcome the ethical and methodological challenges that are often perceived as barriers to child participation in tourism and hospitality research and embrace more than interdisciplinary approaches [29,67]. This review paper thus makes a plea to tourism and hospitality scholars to take children more seriously in their research, particularly when it comes to family unit entrepreneurship, and recommends a future research agenda that is inclusive of their voices. The original contribution of this newspaper then lies in highlighting the gap in cognition and proposing a shift in paradigm towards a 'childist' approach to research, which has significant implications for policy, direction, and planning in tourism and hospitality. A focus on this neglected area of enquiry could so contribute towards a more than sustainable and equitable tourism/hospitality future.

Writer Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C. and H.S.; methodology, A.C.; formal assay, A.C.; writing—original draft preparation, A.C. and H.Due south.; writing—review and editing, A.C. and H.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This enquiry received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Non applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicative.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the language communication obtained from Xiaoxi Ju at Auckland University of Applied science during the article screening procedure.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no disharmonize of involvement.

References

- Carr, N. Children's and Families' Holiday Experience; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gram, Thousand.; O'Donohoe, S.; H.S., H.; Marchant, C.; Kastarinen, A. Fun time, finite time: Temporal and emotional dimensions of grandtravel experiences. Ann. Tour. Res. 2019, 79, 102769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoden, S.; Hunter-Jones, P.; Miller, A. Tourism experiences through the optics of a kid. Ann. Leis. Res. 2016, nineteen, 424–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Carlsen, J. Family unit business in tourism: Land of the Art. Ann. Bout. Res. 2005, 32, 237–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakas, F.E. The political economy of tourism: Children's neglected role. Tour. Anal. 2018, 23, 215–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, H.E.; Cliff, J.East. The pervasive effects of family unit on entrepreneurship: Toward a family embeddedness perspective. J. Bus. Ventur. 2003, 18, 573–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, R.K.; Hoy, F.; Poutziouris, P.Z.; Steier, Fifty.P. Emerging paths of family entrepreneurship research. J. Small Coach. Manag. 2008, 46, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, R.One thousand.; Mishra, C.S. Family entrepreneurship. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2008, 46, 313–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Fernández, M.C.; Serrano-Bedia, A.M.; Pérez-Pérez, M. Entrepreneurship and family business firm enquiry: A bibliometric analysis of an emerging field. J. Pocket-size Bus. Manag. 2016, 54, 622–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordqvist, M.; Melin, L. Entrepreneurial families and family unit firms. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2010, 22, 211–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjei, E.Chiliad.; Eriksson, R.H.; Lindgren, U.; Holm, East. Familial relationships and firm performance: The touch on of entrepreneurial family relationships. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2019, 31, 357–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canosa, A.; Graham, A. Upstanding Tourism Research Involving Children. Ann. Bout. Res. 2016, 61, 219–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, A.; Powell, Grand.A.; Anderson, D.; Fitzgerald, R.; Taylor, Northward.J. Ethical Research Involving Children (ERIC): Compendium; UNICEF Office of Research—Innocenti: Florence, Italy, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Kid (UNCRC); Office of the Loftier Commisioner for Human Rights: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Basu, A. Entrepreneurial aspirations among family business organization owners. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2004, ten, 12–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, J. More than than putting on a performance in commercial homes: Merging family practices and critical hospitality studies. Ann. Leis. Res. 2015, eighteen, 414–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seymour, J. Entertaining guests or entertaining the guests: Children'southward emotional labour in hotels, pubs and boarding houses. In The Politics of Childhood: International Perspectives, Contemporary Developments; Goddard, J., McNamee, S., James, A., Eds.; Palgrave MacMillan: New York, NY, USA, 2005; pp. 90–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth, One thousand.R.F.; Wilson-Youlden, L. Women Tourism Entrepreneurs and the Survival of Family Farms in N East England. J. Rural. Community Dev. 2019, 14, 125–145. [Google Scholar]

- Schänzel, H.; Carr, Due north. Special consequence on children, families and leisure—Offset of ii issues. Ann. Leis. Res. 2015, 18, 171–174. [Google Scholar]

- Small, J. The absenteeism of childhood in tourism studies. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 772–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gram, M. Children as co-decision makers in the family unit? The case of family holidays. Young Consum. 2007, 8, xix–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poria, Y.; Timothy, D.J. Where are the children in tourism research? Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 47, 93–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugosi, P.; Robinson, R.Northward.; Golubovskaya, M.; Foley, Fifty. The hospitality consumption experiences of parents and carers with children: A qualitative report of foodservice settings. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2016, 54, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-Due south.; Lehto, X.; Behnke, C.; Tang, C.H. Investigating children's role in family dining-out choices: Evidence from a coincidental dining restaurant. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2016, 25, 706–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, B. 'Why do kids' menus ever have chicken nuggets?': Children'due south observations on the provision of food in hotels on family unit holidays. Hosp. Soc. 2018, eight, 69–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canosa, A.; Graham, A. Tracing the contribution of childhood studies: Maintaining momentum while navigating tensions. Childhood 2020, 27, 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handel, G.; Cahill, S.E.; Elkin, F. Children and Club: The Folklore of Children and Childhood Socialization; Roxbury Publishing Co.: Los Angeles, CA, Usa, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Canosa, A.; Moyle, B.; Wray, M. Can Anybody Hear Me? A Critical Analysis of Young Residents' Voices in Tourism Studies. Tour. Anal. 2016, 21, 325–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo-Lattimore, C. Kids on board: Methodological challenges, concerns and clarifications when including immature children's voices in tourism enquiry. Curr. Issues Tour. 2015, 18, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schänzel, H.A.; Smith, Grand.A. The socialization of families abroad from home: Grouping dynamics and family unit functioning on holiday. Leis. Sci. 2014, 36, 126–143. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, One thousand.-Y.; Wall, Chiliad.; Zu, Y.; Ying, T. Chinese children's family tourism experiences. Bout. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 29, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.J.H.; Yang, E.C.L.; Khoo-Lattimore, C. Host-children of tourism destinations: Systematic quantitative literature review. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 45, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canosa, A.; Wilson, E.; Graham, A. Empowering immature people through participatory film: A postmethodological approach. Curr. Problems Tour. 2017, twenty, 894–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canosa, A.; Graham, A.; Wilson, Eastward. Growing up in a tourist destination: Negotiating space, identity and belonging. Child. Geogr. 2018, sixteen, 156–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromley, R.D.; Mackie, P.Thou. Child experiences as street traders in Republic of peru: Contributing to a reappraisal for working children. Child. Geogr. 2009, 7, 141–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Labour Arrangement. Kid Labour: Global Estimates 2020, Trends and the Road Forward. 2020. Available online: https://world wide web.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_norm/---ipec/documents/publication/wcms_797515.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Grier, B. Kid labor and Africanist scholarship: A disquisitional overview. Afr. Stud. Rev. 2004, 47, ane–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beazley, H.; Ball, J. Children, youth and development in Southeast Asia. In Routledge Handbook of Southeast Asian Development; McGregor, A., Police force, L., Miller, F., Eds.; Routledge: London, Uk, 2017; pp. 211–223. [Google Scholar]

- Beazley, H.; Miller, A. The Art of Non Been Governed: Street Children and Youth in Siem Reap, Cambodia. In Politics, Citizenship and Rights; Academy of the Sunshine Coast: Queensland, Australia, 2015; pp. 263–290. [Google Scholar]

- Estrada, E. Kids at Piece of work: Latinx Families Selling Food on the Streets of Los Angeles. Lat. Stud. 2021, 19, 137–139. [Google Scholar]

- Invernizzi, A. Perspectives on children's piece of work in the Algarve (Portugal) and their implications for social policy. Crit. Soc. Policy 2005, 25, 198–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josefsson, J.; Wall, J. Empowered inclusion: Theorizing global justice for children and youth. Globalizations 2020, 17, 1043–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terenzio, F. The African movement of working children and youth. Development 2007, 50, 68–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebel, K.; Invernizzi, A. The Movements of Working Children and the International Labour Organization. A Lesson on Enforced Silence. Kid. Soc. 2019, 33, 142–153. [Google Scholar]

- Balagopalan, Due south. Childhood, civilisation, history: Redeploying 'multiple childhoods'. In Reimagining Babyhood Studies; Spyrou, Southward., Rosen, R., Cook, D.T., Eds.; Bloomsbury Bookish: London, UK, 2019; pp. 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez, E. Decolonising concepts of participation and protection in sensitive research with immature people: Local perspectives and decolonial strategies of Palestinian research advisors. Childhood 2021, 28, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canosa, A.; Van Doore, K.E.; Beazley, H.; Graham, A. Children's Rights in the Tourism Industry. Int. J. Child. Rights. Forthcoming.

- Arksey, H.; O'Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005, 8, xix–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O'Brien, K.Chiliad.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, G.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segrado Pavon, R.G.; Cruz Jiménez, G.; Castillo Nechar, Thou. Child Employment, a Controversial Issue; Analysis in Two Touristic Destinations. J. Tour. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 7, 186–194. [Google Scholar]

- Weiler, B.; Martin, V.Y.; Canosa, A.; Cutter-Mackenzie, A. Generation Y and protected areas: A scoping study of research, theory, and time to come directions. J. Leis. Res. 2018, 49, 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilbery, B.; Bowler, I.; Clark, 1000.; Crockett, A.; Shaw, A. Farm-based Tourism every bit an Alternative Farm. Reg. Stud. 1998, 32, 355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Jurinčič, I.; Bojnec, Š. Wine tourism development: The case of the wine district in Slovenia. Tourism 2009, 57, 435–448. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, J.D.; Supratikno, H.; Pramono, R.; Purba, J.T.; Bernarto, I. Nurturing transgenerational entrepreneurship in ethnic Chinese family SMEs: Exploring Indonesia. J. Asia Bus. Stud. 2019, xiii, 294–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Far, Thou.T.; Sabella, A.R. Entrepreneuring equally an everyday form of resistance. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 1212–1235. [Google Scholar]

- Kawharu, Chiliad.; Tapsell, P.; Wood, C. Indigenous entrepreneurship in Aotearoa New Zealand. J. Enterprising Communities People Places Glob. Econ. 2017, 11, 20–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, P. The Benefits of Family Employment in Indigenous Restaurants: A Case Study of Regional Victoria in Commonwealth of australia. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2011, xvi, 537–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Fifty.A. The Family Farm Business organization? Insights into Family, Business and Ownership Dimensions of Open up-Farms. Leis. Stud. 2007, 26, 357–374. [Google Scholar]

- Zagkotsi, S. Family and the Rate of Tourism Development as Factors Generating Mobility in the Greek Tourism Sector. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Due west. The Nature and Roles of Small Tourism Businesses in Poverty Consolation: Evidence from Guangxi, China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2009, fourteen, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Getz, D.; Carlsen, J.; Morrison, A. The Family unit Business in Tourism and Hospitality; CABI Publishing: Cambridge, MA, The states, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Wall, J. From childhood studies to childism: Reconstructing the scholarly and social imaginations. Child. Geogr. 2019, ane–fourteen. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo-Lattimore, C.; delChiappa, G.; Yang, M.J. A family for the holidays: Delineating the hospitality needs of European parents with immature children. Young Consum. 2018, 19, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdillon, M. Children and work: A review of current literature and debates. Dev. Chang. 2006, 37, 1201–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spivak, G.C. Tin the Subaltern Speak? In Marxism and the Interpretation of Civilisation; Nelson, C., Grossberg, 50., Eds.; Macmillan Teaching: Basingstoke, Great britain, 1988; pp. 271–313. [Google Scholar]

- Canosa, A.; Graham, A.; Wilson, Due east. Growing up in a tourist destination: Developing an environmental sensitivity. Environ. Educ. Res. 2020, 26, 1027–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canosa, A.; Graham, A.; Wilson, E. Progressing a Child-Centred Inquiry Agenda in Tourism Studies. Tour. Anal. 2019, 24, 95–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1. PRISMA option and inclusion strategy (adapted from Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, and Altman 2009).

Figure 1. PRISMA option and inclusion strategy (adjusted from Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, and Altman 2009).

Figure two. Land distribution of studies included in the sample.

Effigy two. State distribution of studies included in the sample.

Table 1. Thematic Analysis.

Table 1. Thematic Analysis.

| Authors | RQ1: Children'southward Role in Tourism Family Entrepreneurship | RQ2: Social Constructions of Childhood |

|---|---|---|

| Bakas, 2019 |

|

|

| Basu, 2004 |

|

|

| Bosworth & Wilson-Youlden, 2019 |

|

|

| Kawharu, Tapsell & Woods, 2017 |

|

|

| Strickland, 2011 |

|

|

| Seymour, 2005, 2015 |

|

|

| Wilson, 2007 |

|

|

| Zagkotsi, 2014 |

|

|

| Zhao, 2009 |

|

|

| Publisher'south Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 past the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC Past) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Source: https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/22/12801/htm

0 Response to "Kids at Work: Latinx Families Selling Food on the Streets of Los Angeles"

Post a Comment